Downsizing the American Dream of Home Sweet Home

By Justin LaBerge, with additional information provided by Colorado Country Life

A house, two kids, a manicured lawn and a well-maintained fence to keep it all safe. For years, that was the dream to which many Americans aspired.

But if you scroll through your social media feed or watch one of the countless reality shows about real estate and housing, you’ll notice that many folks are eschewing that traditional American home in favor of alternative accommodations.

The reasons people prefer these nontraditional structures are as diverse as the buildings themselves. Some want to simplify and declutter their lives. Others want to save money and energy. Here’s a look at a few of the more popular non-traditional home designs that might be coming to a neighborhood near you.

Tiny houses look like real houses, with square corners, traditional siding materials and pitched roofs. They typically offer 100 to 130 square feet of living space, and must be less than 8 feet 6 inches wide and 13 feet 6 inches tall to legally drive on the road without a special permit.

TINY HOUSES

The tiny house trend got its start with a man named Jay Shafer who built his first miniature house on wheels in Iowa in 1999. Shafer is a person who liked to challenge the status quo, and after living in a variety of nontraditional spaces over the years, he started drawing plans for imaginary houses.

Over time, the designs got simpler and smaller, and he was inspired to build one for real when he learned they didn’t meet building codes. He took that as a challenge and realized that if he built the house on a prefabricated, street legal trailer, it would be considered a trailer load and not a house and, thus, not subject to building codes.

This nonconformity makes tiny houses a controversial issue in many communities, and local governments struggle to balance individual rights, local codes and public safety. Their nontraditional design also makes tiny houses more difficult to finance and insure, although options for both are available.

Despite these challenges, thousands of people purchased do-it-yourself plans as well as manufactured tiny houses from Shafer and other designers.

Unlike mobile homes or camping trailers, tiny houses look like real houses, with square corners, traditional siding materials and pitched roofs. They typically offer 100 to 130 square feet of living space and must be less than 8 feet 6 inches wide and 13 feet 6 inches tall to legally drive on the road without a special permit. The weight varies based on the length and rating of the trailer, but tiny houses are typically much heavier than camping trailers because they are made from traditional building materials.

Tiny house living continues to pick up in popularity in Colorado. Several companies offer manufacturing services to suit what buyers long for in a little home, including Colorado Springs-based Tumbleweed Tiny House Factory, Durango-based Rocky Mountain Tiny Houses and Fort Collins-based MitchCraft Tiny Homes.

Now trending throughout the United States are tiny home communities where like-minded little home lovers can enjoy the niceties of living in a neighborhood, but on a much smaller scale than traditional living. One such community located in Fairplay offers tiny house owners a community clubhouse as well as nearby access to Breckenridge Ski Resort, fly-fishing hot spots, ample hiking and many more outdoor adventure options.

A new tiny house planned development popped up in Salida as well, where the manufacturing of 200 rental units is currently under way. Located along the Arkansas River, the tiny house community will feature a community building, exercise facility, restaurant, 96 storage units and more when completed. Sprout Tiny Homes is developing this community and has plans to break ground in Walsenburg where it will build a 33-unit tiny home community to address the need for housing in the area.

CONTAINER HOMES

The shipping container became a political symbol for many people in recent years. To some, they are a symbol of the decline of American manufacturing. To others, the containers are tools that connect us to a globalized economy and lower costs of many consumer goods.

But to a group of architecture enthusiasts, the shipping containers stacked on cargo boats, carried by freight trains and pulled by trucking rigs are grown-up Lego blocks waiting to be turned into homes.

The first container buildings were built by those looking for a fast, simple and low-cost way to provide shelter. Containers are strong, easy to transport and, thanks to global trade, abundant.

Over time, what started as a clever way to recycle old containers and quickly build inexpensive structures changed into an architectural trend. The modular, boxy aesthetic of shipping containers gives container homes a modern look that many find appealing. Today, container homes range in size and complexity from modest, inexpensive, utilitarian dwellings to large, highly customized, luxury homes.

Container homes are getting attention in Colorado as well. Rhino Cubed recycles and repurposes out-of-commission shipping containers to create compact homes that make a big impression. The Louisville-based company sells containers with minimal amenities such as windows, doors and lead-free certification; midstream amenities with all the above plus hickory floors, finished walls and insulation; or all-you-could-expect-from-a- house perks, such as a full kitchen, storage, water disposal, bunk beds, exterior paint and more.

Container home enthusiasts say the three keys to a successful project are understanding all local building codes and safety regulations before starting the project, hiring a contractor that has previous experience with this unique form of construction and purchasing the correct type of container.

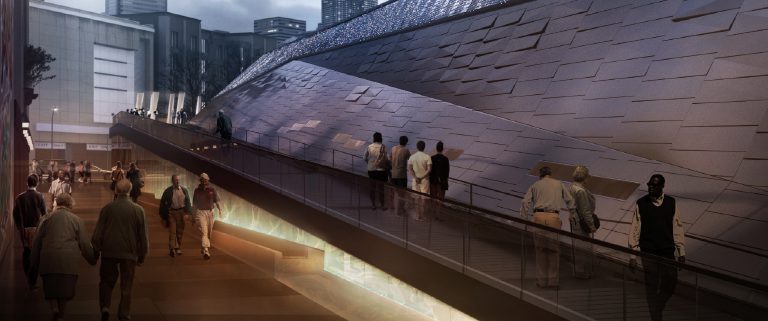

Monolithic domes offer homeowners the high ceilings and large open floor plans that are so popular today. They are also highly efficient, requiring about a quarter of the energy required to heat and cool a similarly sized traditional structure. Photo credit: Kevin McGuckin

OLD HOUSE, NEW TRICKS

The options are plentiful when it comes to miniature domiciles in Colorado and beyond. From tipis to monolithic homes to yurts, home buyers can choose what suits their fancy. At Colorado Yurt Company, for example, potential buyers can build a yurt from scratch using their Yurt Price Calculator. Select the requirements for your yurt, such as door type, window options and snow and wind load packages, and watch as it calculates your costs.

Even traditional houses aren’t immune to the trend of alternative construction techniques. Advances in technology transformed the manufactured housing business as well. In addition to the classic mobile home and newer modular home designs, high-end custom homes created from prefabricated panels built in a factory can be purchased and assembled on site. This can save up to 15 percent over the cost of a traditional home.

So, whether it’s a tiny home, a yurt, a container or a prefabricated home, the American dream of home ownership now comes in many shapes and sizes.

Justin LaBerge writes on consumer and cooperative affairs for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association.