By Paul Wesslund

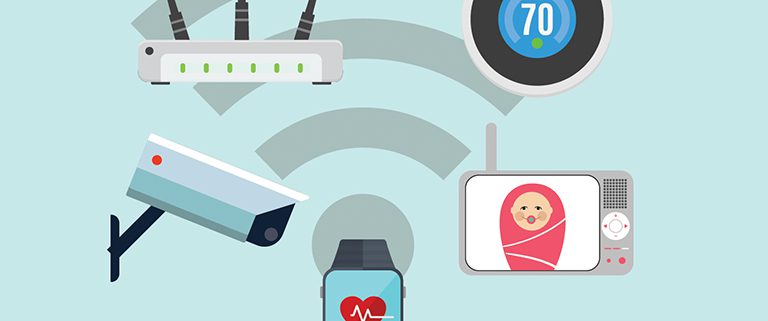

If you ever want to see one of the biggest changes going on in the world today, look around your home. Your smartphone, video gaming system, security camera, fitness bracelet, thermostat and even your television could be part of a vast, interconnected group of devices that goes by the clunky name of the “internet of things.”

The term refers to anything connected to the internet, which covers a lot of gadgets and will soon cover even more. Today, you can purchase lightbulbs that dim with the sound of your voice or from the press of a button on your smartphone. A 2014 report by the investment firm Goldman Sachs predicted the number of internet-connected devices could grow 10 times by 2020, to as many as 28 billion “things.”

While this growth may seem like the latest trend, it was recognized more than 30 years ago. Credit for naming it goes to Peter T. Lewis, co-founder of Cellular One. In a 1985 speech he said, “The internet of things, or IoT, is the integration of people, processes and technology with connectable devices and sensors to enable remote monitoring status, manipulation and evaluation of trends of such devices.”

Low prices versus security

In other words, the rapid rise in the number of internet-connected devices has been building for decades, says Tim Heidel, deputy chief scientist with the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association. “The ‘internet of things’ is the latest buzzword that reflects a long-term trend,” Heidel says. “Ten years ago, you may have had six or eight or 10 devices on the wireless router in your home. Now, that number can go as high as 25 or 30 devices.”

Heidel credits lower costs for ramping up this high-tech revolution, which can make life more convenient and fun, and even increase energy efficiency with new ways to control heating, cooling, lighting and other electricity users.

“The cost of including communications in the devices has come down dramatically. Twenty years ago, you could only afford an ethernet port or Wi-Fi in a computer,” Heidel says. “Now, we’re getting to the point where it costs literally only pennies to include that capability in any device imaginable.

“So what’s changing here is the number of devices. Once you have a critical mass of all the places that are capable of communicating, they can then start communicating with each other.

All of this promises convenience and services, but in the pursuit of extremely low costs, sometimes there’s the opportunity to cut corners on security,” Heidel adds.

A stunning example of security problems with the “internet of things” happened last October when hackers crashed dozens of websites in the United States for most of a day, including well-known names like Netflix and Twitter. Incredible as it seems, that attack may have been aided by a device in your own home.

Here’s what happened Friday, October 21: Hackers already scanned the world for devices vulnerable to infection by malicious software that allowed them to take control of hundreds of thousands of home routers, baby monitors, printers and network-enabled cameras. Using that “botnet,” the hackers flooded websites with so many messages the sites shut down for several hours in what is called a “denial of service” attack.

Cyber safety tips

There are ways you can reduce your risk from hackers hijacking your internet-connected devices, says Cynthia Hsu, cyber security program manager with NRECA.

“Understand what you’re buying,” Hsu says. “If you have a choice between two vendors who are producing a product and one takes security seriously and the other doesn’t, use your money to buy a product that takes security seriously. If consumers are not willing to pay for security, the manufacturers have no incentive to build it.

“The criminal element is rapidly escalating the innovation of new ways of attack.” If you have a router for wireless internet in your home, Hsu says, “make sure you patch your router’s software whenever security updates are available so it’s protected as new vulnerabilities are discovered.”

Other security steps Hsu recommends:

• Install firewalls in your home network.

• Change the default passwords regularly in devices you purchase.

• Disconnect gadgets when they’re not being used. “Not everything needs to be plugged into the internet all the time,” she says.

Keep in mind that the electronics in your home can not be accessed from outside without you allowing it. For example, your electric utility cannot access your refrigerator’s energy usage unless it is a smart refrigerator that you allow access to and it is connected to one or more online applications.

The folks at your local electric co-op can offer expertise in managing the promise and the problems of what is called the “internet of things,” and they can answer questions about efficient energy usage. NRECA, your co-op’s national association, is researching some of the newest devices to understand how they can be used for energy efficiency.

“NRECA does a lot of research to help guide, deploy and test these devices,” says Venkat Banunarayanan, NRECA’s senior product development manager. “These projects are looking at how to use these devices in the ‘internet of things’ to bring value to the co-op and its members.”

Paul Wesslund writes on cooperative issues for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association.