Reasons You May or May Not Want an EV for Christmas

By Paul Wesslund

Wondering if an electric vehicle is a good gift idea for you or your significant other this Christmas? The answer could depend on where you live.

Electric vehicles account for just 1.2 percent of the U.S. vehicle market, but sales are booming, growing 25 percent last year. And they’re getting better and cheaper as researchers improve the batteries that power them. Here’s a guide to help you decide if an electric car is for you — or if you just want to be smarter about one of the next big things in energy.

The first thing to realize about electric cars is they can drive more than enough miles for you on a single charge, even if you live out in the wide-open countryside.

LOCATION ISSUE 1: THE DISTANCE MYTH

Try keeping track of your actual daily use, advises Brian Sloboda, a program and product manager at the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association.

Try keeping track of your actual daily use, advises Brian Sloboda, a program and product manager at the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association.

“If you’re an insurance salesman, you’re logging a lot of miles, so an electric car’s not going to be for you,” he says, noting that a typical range for an electric car today is more than 100 miles, and ranges of 150 to 250 miles are becoming common. “But if you look at how many miles you drive in a day, for most people in the United States, even in rural areas, that number is under 40 miles per day. So if your car has a range of 120 miles, that’s a lot of wiggle room.”

According to the Federal Highway Administration, the average American drives 25 miles per day, and for rural areas that average is 34 miles a day.

Sloboda says another reason it’s worth thinking realistically about your daily mileage comes from the most likely way an electric car would be refueled. When an electric car is done driving for the day, you can plug it in to recharge overnight. Essentially, you’re topping off the gas tank while you sleep, giving you a fully-charged battery every morning.

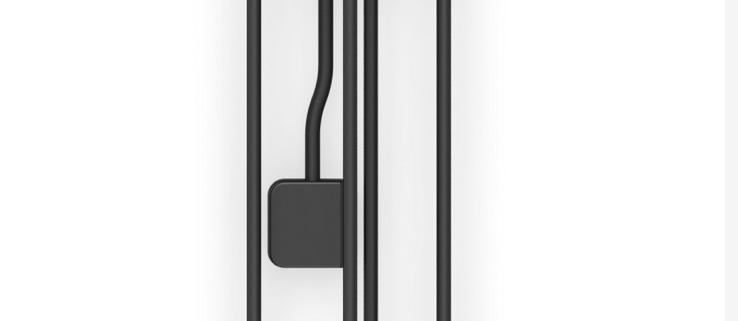

There are three ways to charge an electric car:

Level 1 — The simplest charging technique is to plug the car into a standard home outlet. That will charge the battery at a rate that will add two to five miles to its range each hour. That’s pretty slow, but Sloboda notes the battery might start the charging session already partly charged, depending on how far it is driven that day.

Level 2 — Faster charging will require a professional installer to upgrade the home’s voltage for a unit that will add between 10 and 25 miles of range for each hour of charging — a rate that would fully charge the battery overnight. Sloboda says installing a Level 2 charger in a house or garage would run $500 to $800 for the equipment, plus at least that much for the labor. Timers can also be used to charge the vehicle in the middle of the night when electric consumption is typically lower.

Level 3 — DC (direct current) fast charge requires specialized equipment more suited to public charging stations and will bring a car battery up to 80 percent of capacity in 30 minutes. Sloboda warns this high-speed technique should only be used for special long-distance driving, since it can degrade the battery over time. That’s also why DC chargers shouldn’t be used to bring the battery up to 100 percent.

LOCATION ISSUE 2: OFF-PEAK ELECTRIC RATES

What you pay to charge your electric car could also depend on where you live, Sloboda says. He advises checking to see whether your local electric co-op offers a lower rate to charge an electric vehicle overnight, when the utility has a lower demand for electricity.

“It’s different depending on where you are in the country,” Sloboda says. Some local co-ops have fairly stable electric demand throughout a typical day, so they may not offer a special electric vehicle rate. He says there are areas of the country where the on-peak, off-peak difference in price is extreme, so it might make financial sense for the utility to offer an overnight charging rate.

Another factor affecting the economics of an electric car is, of course, the cost of the vehicle.

“These cars are really in the luxury and performance car categories,” Sloboda says. As electric cars improve, projections put their cost coming down to match conventional vehicles by about the year 2025. But today, the average electric car costs close to $40,000, compared with less than $30,000 for several internal combustion engine vehicles.

LOCATION ISSUES 3 AND 4: ENVIRONMENT AND GEOGRAPHY

For many people, one of the biggest selling points for electric cars is their effect on the environment, and that can also depend on where you live.

The sources of electricity for a local utility vary across the country — some areas depend heavily on coal-fired power plants, others use larger shares of solar or wind energy. One major environmental group analyzed all those local electric utility fuel mixes and determined that, for most of the country, electric vehicles have much less of an effect on the environment than conventional vehicles. That study by the Union of Concerned Scientists shows that in the middle part of the country, driving an electric vehicle has the equivalent environmental benefits of driving a gasoline-powered car that gets 41 to 50 miles per gallon. For much of the rest of the country, it’s like driving a car that gets well over 50 miles per gallon.

“Seventy-five percent of people now live in places where driving on electricity is cleaner than a 50 mpg gasoline car,” the report from the Union of Concerned Scientists states.

Other local factors that will affect an electric car’s performance include climate and geography, Sloboda says. The range of the vehicle will be affected by whether you regularly drive up and down mountains or make a lot of use of the heater or air conditioner.

Sloboda concedes that electric vehicles are not for everybody. One limit to their growth is that no major carmaker currently offers an especially popular choice: a pickup truck. Although, the development of electric pickups is under way at Atlis Motor Vehicles and Workhorse group, and discussions show Tesla is considering developing an electric pickup as well.

Sloboda suggests possible advantages of an electric pickup: a heavy battery in the bottom would lower the center of gravity for better handling, and at a remote work site the battery could run power tools.

Paul Wesslund writes on consumer and cooperative affairs for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association.